Welcome to the beginning!

Genesis chapter 1 is one of the most contentious and divisive passages in the entire Bible. But in all the debate – history, legend, science, or fact – what really matters? Why is this chapter so important?

Today, we will focus on the story itself, and why – all other questions and debates aside – knowing the story is so important.

Also, Genesis 1 is a profoundly gorgeous work of art. That alone makes it worthy of our time and attention.

Let’s begin with… the story itself. Genesis 1:1-2:4 recounts a whole, self-contained creation story, distinct (not necessarily contradictory) from the story told in Genesis 2 and 3.

A while back, when I was in the midst of some personal turmoil about the discovery of two separate creation stories placed back-to-back in Genesis 1-3 (we’ll get to that next week…), my mother said to me: “You know, Genesis 1 has always kind of struck me as a lullaby Eve would have sung to her children.

That idea stuck with me.

Whether originally set to music or not, the Genesis 1 story displays several poetic and rhythmic qualities – most notably, repeated refrains like “and there was evening and there was morning,” and a mirrored structure to the entire chapter itself (see the Artistic Framework section below). The idea that it could have originally been a song is not farfetched.

Regardless, my mother’s suggestion never left my head. So, I went with it. Below is my own translation of Genesis 1:1-2:4, set to music, sung as a mother’s lullaby. Take a listen.

“A great wind, a great calm, a great fear / an unspeakable power is here…”

The lyrics of a song written by the greatest songwriter of modern times—as far as I am concerned—a man named Michael Card. His songs are simple—like a lot of Bible stories—but layered in meaning, like Bible stories. Including this song, A Great Wind, a Great Calm, a Great Fear, inspired by this passage we read today from Mark.

This moment when these experienced fishermen, well aware of how violent and dangerous the Sea of Galilee could be, are swept up in this terrible storm in the middle of the night. And in response, Jesus just—well, first of all, he’s asleep, doesn’t even notice as the boat is filling with water. And then, when made aware of the situation, he stands up, says “Be still,” and then all is just still (Mark 4:35–39).

And then Jesus goes on to ask: So, what were you so worried about, exactly?

A Great Storm, A Great Calm, A Great Fear

In an interview about this song that he wrote about this story from Mark, Michael Card observed that in Mark’s version of this event, the Greek word great or large—megon or megale—is used three times. First, there is a “great storm.” Then Jesus speaks, and there is a “great calm.” And then after that—despite all the terror they must have felt during the storm itself—it is after Jesus speaks, after the “great calm,” that we are told the disciples experienced a “great fear” (Mark 4:37–41).

And actually, the Greek drives this point home in a way that is somewhat awkward in English. The Greek doesn’t just use the word “great.” The Greek repeats the word fear as a verb and as a noun. Mark 4:41 literally reads: “And they feared a great fear” (Mark 4:41, literal rendering).

And why?

After the danger has passed, the storm has ended, the lake is calm again—why is this the moment to fear a great fear?

“A great wind, a great calm, a great fear / an unspeakable power is here / far beyond the darkness and the waves / there is a very real reason to be afraid…”

There are layered meanings, stacked meanings in these simple words—just as there are in the actual text of the story Michael Card was writing about Mark tells us: “And they feared a great fear, and said to one another, ‘Who then is this, that even the wind and the sea obey Him?’” (Mark 4:41).

Who Can Command the Wind and the Sea?

I’m starting with this passage from Mark today because it’s the perfect illustration of why knowing stories like Genesis 1 really matters.

When you know the stories and the symbolic vocabulary on which they are built, you realize that this is not a rhetorical question. It’s not just a statement of wonder or amazement. It’s not a question with no answer. In fact, it’s a question that has one and only one answer, which the disciples themselves—and Mark, the Gospel writer—are all well aware of, because it is an answer that comes from this shared symbolic vocabulary that storytellers have been drawing on for thousands of years before Jesus was born.

And when you know that symbolic vocabulary, you realize—it is, in fact, a direct claim to divinity.

Because in this symbolic vocabulary of first-century storytelling, there are indeed beings who can command the wind and the sea.

They’re just not human beings.

In fact, in Judaism—monotheism—there is only one such being. The One Being. Who in Hebrew history once commanded the floodwaters to cover the earth, once split the Red Sea, split the Jordan River, sent a sea storm after Jonah, is described in places like Psalm 104 as riding on the storm clouds (Genesis 7; Exodus 14; Joshua 3; Jonah 1; Psalm 104:3).

In first-century Jewish thought—as still in Judeo-Christian thought today—there is only one answer to the disciples’ question in Mark 4.

The One at the Beginning

“And the earth was formless and void, and darkness was upon the face of the deep, and the Spirit of God was moving over the face of the water…” (Genesis 1:2)

Look back at Genesis 1. Listen to or read it again for best results. Pay attention this time through to the role of water, specifically…

Chaos, the Deep, and the Defeated Waters

The conquered water, that is.

There’s a piece in the creation story that is not recorded in Genesis, but was well known in that symbolic vocabulary of the ancient Near East. The part of the story where the storm god conquers the great Sea Dragon, Tiamat, tears her corpse in half, and uses those halves to create the sky and the earth.

Yes, according to the Babylonians, the ocean is a primordial chaos monster, and we are all living inside her… carcass.

Mythology’s fun, y’all.

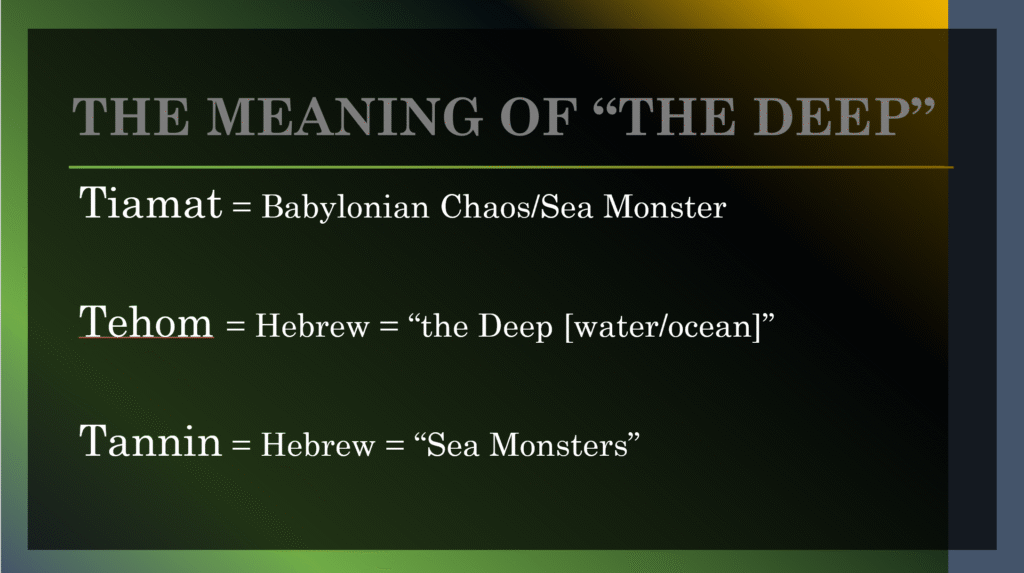

Now Tiamat is the Babylonian word. It refers to the abyss of salt water, also known as “the Deep.”

In Hebrew, the word is tehom, as in v’choshek al panay tehom—“and darkness was upon the surface of the deep” (Genesis 1:2). Linguistically, these two words, Tiamat and Tehom, are probably related.

And there’s another one. Day 5 of Genesis 1, when God creates the fish, right? The creatures that live in the ocean. Some of which are called, in Hebrew, tanninim—that’s the plural; the singular is tannin. It gets translated a variety of ways, like “sea creature” or “creatures of the deep” (Genesis 1:21).

It means serpent, dragon, or—my translation from the song—sea monster.

Again, linguistically, probably related to the Babylonian name of this chaos, ocean, dragon goddess Tiamat, the one defeated by the storm god at the beginning of the world.

Creation Without Violence

Genesis 1, of course, skips this part. There is no cosmic war at the beginning of the universe according to our story. The universe does not begin in violence. War and the subsequent desecration of a corpse are not the means of creation in our story. And that is significant.

It says a lot about who the Hebrew God is as opposed to the gods of the surrounding nations. Who our God is and how He works.

In Genesis 1, God just creates. And no, God does not create the universe out of a sea dragon carcass. But God does create the universe by dividing the waters.

Let’s go through the actual Genesis story a little more closely.

The Days of Creation and the Defeat of Chaos

In the beginning, there was the water—the Deep, the Tehom, the Tiamat—chaos, oblivion, destruction. And there was God.

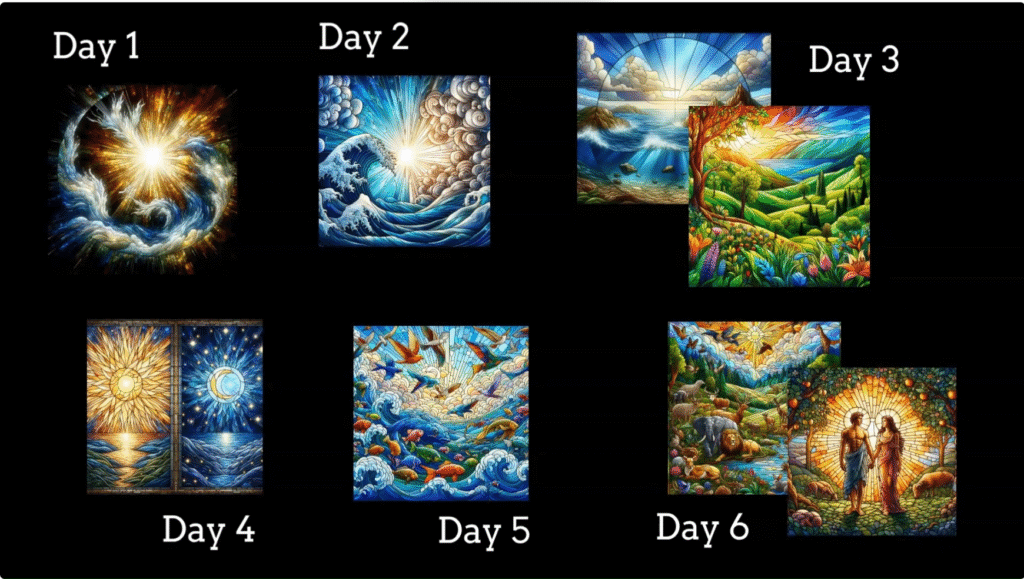

Day 1: God creates light.

Day 2: God creates the sky—but what does that actually mean?

We have to train ourselves when reading these stories to see things the way the ancients imagined them. The earth is not a globe orbiting a star orbiting a galaxy in a vast universe as we now know it to be. To the ancient mind, earth and sky was the totality of existence.

And what does “earth and sky”—that is, all of reality—look like at this moment in the story?

Read the words. Focus on what they are actually saying. Imagine with them the picture those words are actually painting.

There is no planet, no earth as we understand it, no sun outside to be orbited—the sun isn’t even created until Day 4 (Genesis 1:14–19).

As of Day 2 in Genesis chapter 1, the totality of reality is light and water.

And on Genesis Day 2, God divides the water—just as Marduk, the Babylonian creator god, divides the two halves of the sea dragon—who was also the personification of water.

Again, this is a shared symbolic vocabulary, and the point is power.

“An unspeakable power…” (Michael Card)

The power to defeat oblivion itself.

In the center of the endless water, God creates this barrier that God then names the sky. We translate it various ways—most of those ways, like expanse, are influenced by our modern scientific understanding of what the atmosphere above this planet actually is.

What the Hebrew word indicates is a solid barrier to hold the waters above up over the waters below—creating this space.

Space in which more things can now be created.

Where there was only chaos before, now is possibility. Because of the One Being in all of existence who has power over the waters—power to split the water.

The One whom even wind and sea obey.

From Chaos to Life

Day 3, Part 1: There are actually two parts to Day 3, and also two parts to Day 6.

But Day 3, Part 1: God goes even further. God has split the water in half. God has already, in other words, defeated chaos. And now God assigns what remains of chaos to specific boundaries. This far and no farther.

The sea—chaos and oblivion—fully conquered and utterly subdued.

And the result, again, is the potential for more and more complex creation—the appearance of dry land, more space in which things can now be created (Genesis 1:9–10).

Day 5: God doesn’t just defeat oblivion or trap oblivion within certain boundaries. God now fills oblivion with life—particularly these tanninim, the sea monsters.

And this really does matter. Because in the Babylonian and other Mesopotamian versions, Tiamat creates the sea monsters. It’s actually a highly significant part of the story when Tiamat creates the sea monsters to be her army in the war she is waging against the other gods.

God’s power over oblivion in Genesis is even greater—in fact, far greater—than that of Babylon’s Marduk or any other high god in any other myth.

The gods of the myths hold the powers of oblivion and darkness at bay—brutalize them, desecrate them, chain them up at the bottom of the ocean as prisoners for all eternity who might still escape at any moment and wreak havoc and desolation on human life. That is the consummate threat lurking inside most ancient creation myths.

The God of Genesis just… speaks over them, into them, about them.

Before the God of Genesis, these terrible, monstrous forces don’t really seem to be monsters at all.

They’re just creatures.

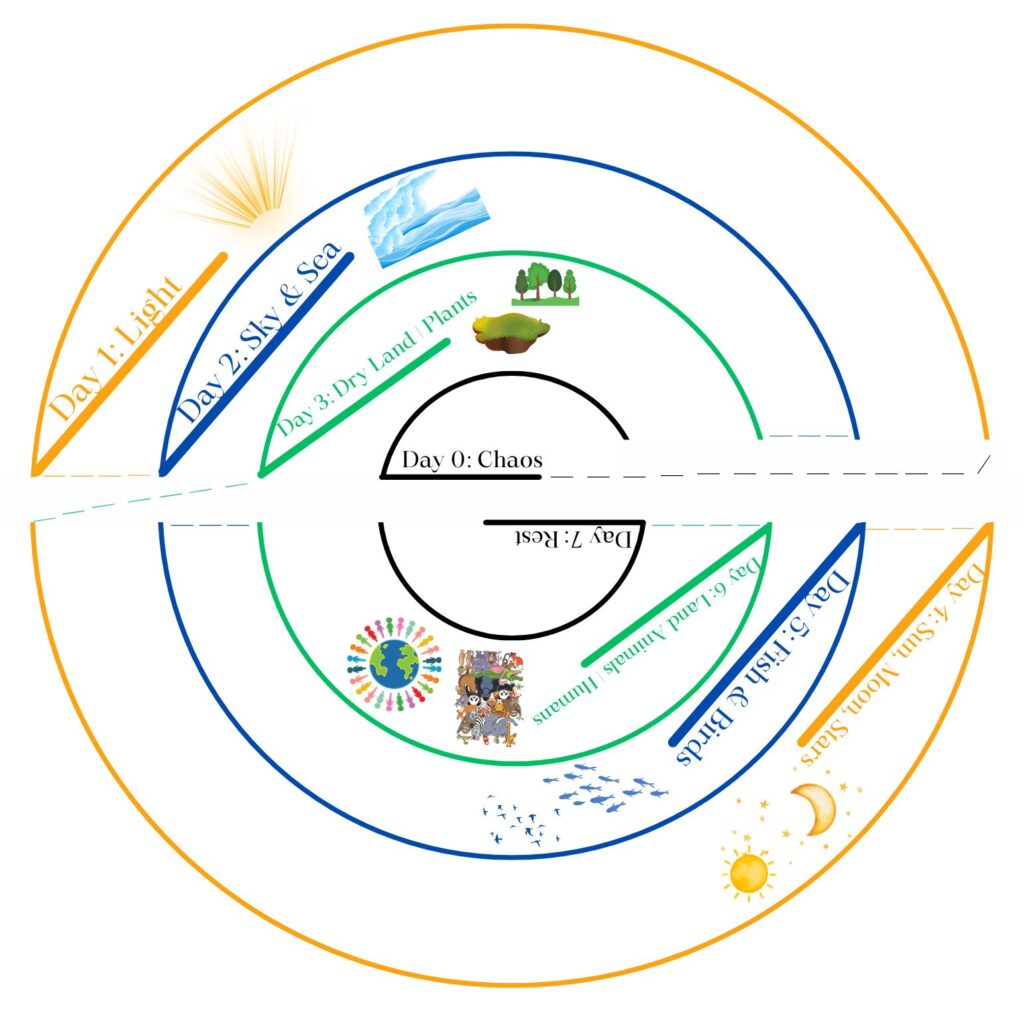

The Structure of Genesis 1: Sacred Architecture

Last thing this morning: We have to talk about the actual structure of Genesis chapter 1.

-

Day 0 – Chaos and oblivion reign

-

Day 7 – Peace, order, and rest reign

-

Day 1 – Light

-

Day 4 – The creatures of light: sun, moon, and stars (considered creatures—gods or angels—in the ancient world)

-

Day 2 – Sky and sea

-

Day 5 – The creatures that live in sky and sea: birds and fish

-

Day 3 – Part 1: dry ground; Part 2: plants

-

Day 6 – Part 1: the creatures that live on dry ground and eat the plants;

Part 2: the ultimate creature that lives on dry ground and eats the plants and has dominion over all other creatures

The mirrored structure you see illustrated here represents perfection.

The even number of days balanced around the prime number 7—a number that in itself represents perfection—represents perfection, with literal nothingness, Day 0, trapped outside that bubble of perfection.

God resting on the seventh day, this number that again represents perfection, standing opposite the nothingness of Day 0, represents perfection.

Two distinct creations on Day 3—another prime number that represents perfection—and on Day 6—the double of the prime number 3 and therefore perfection doubled—all of this again perfectly balanced and symmetrical.

Are you catching the theme here yet? The symbolic architecture. The very intentional literary crafting that can only be adequately described as art.

The Rhythm and Meaning of Creation

Another thing you notice when you read the whole story is that it builds on itself as you go. Each creative act leads naturally into the next in this unbroken rhythm, accented by those repeated refrains: “And there was evening and there was morning…” “And God said…” “And God saw…” “And it was so…” “And it was good…” (Genesis 1).

But beyond even that, there’s an energy running throughout that you can feel building as the days progress.

- We start Day 1: simple—light, that’s all.

- Day 2: the energy builds.

- Day 3: it builds again; things are becoming more and more complex.

- Day 4: actually the longest day word-wise.

- Day 5: even more energy; things are moving on their own now.

- Day 6: two creative acts—humanity, God’s image, blessings, dominion, instructions. The push to the end of the work, creation now fully immersed and interacting with itself and self-sustaining.

- And then Day 7 comes as a great, deep breath… All that tension released. Accomplished. Done.

There’s a rhythm to it. A beat. A cycle—work building to accomplishment and then rest—that we are supposed to emulate in our own lives still today.

The Unspeakable Power

This is a profound work of art.

None of it is accidental. The structure, symmetry, rhythm, symbolic numbers, themes of light and darkness and order and chaos and water and creation—all of it is designed and crafted to build together to one inescapable conclusion, the ultimate point and reason for the story.

And that point is “an unspeakable power.”

The kind of power that only an eternal Creator who exists outside the limitations of time, space, and oblivion itself could possibly have.

The unspeakable power in that boat that night with the disciples (Mark 4:35–41).

The point of Genesis 1 is God as the unspeakable power—beyond the need for war or violence—crafter of order, opposite of accident. And the secondary point: humanity, created in the image of that unspeakable power—created as the opposite of an accident (Genesis 1:26–27).

Symmetry, artistry, theme, literature, emotion, and meaning—these are the things to look for in the stories, because these are the things that come back around in the Bible, in places like Mark 4.

And that is what I want to leave you with this morning—what I want to impress on you this morning, if nothing else, especially as we move on here into Genesis 2 and 3.

That, and this image.

Genesis chapter 1 is pure art, you guys. I mean, there’s really no wonder it was quoted or referenced so often in the New Testament. The imagery in itself is gorgeous. From concept to structure to the individual words and repeated refrains, it is gorgeous.

Please appreciate it for that, if for nothing else.

And do appreciate it for the other things, too.